Ferragosto, celebrated on 15th August, stands as one of Italy’s most revered and widely observed holidays. It is a day that embodies the confluence of historical, cultural, and religious elements, offering a vivid snapshot of Italy’s rich and multifaceted heritage.

The name itself hints at its deep historical roots, deriving from the Latin ‘Feriae Augusti’, which translates to ‘Augustus’s holiday’. This term traces back to the reign of Emperor Augustus, who established the festival in 18 BCE. However, the holiday’s significance has evolved dramatically over the millennia, absorbing various cultural and religious influences.

Today, Ferragosto continues to be a highlight of the Italian summer, a day when families come together, towns and cities host lively festivals, and the entire nation takes a collective pause to enjoy the height of the summer season.

Ancient Roman Origins

The origins of Ferragosto are deeply embedded in the history of ancient Rome, reflecting the interplay between statecraft, culture, and society. Established by Emperor Augustus in 18 BCE, Ferragosto was part of a broader initiative to consolidate his power and create a unified Roman culture and helped cement the emperor’s role as a bringer of peace and prosperity. Augustus would later, in 8 BCE, rename the entire month of Sextilis after himself, like Julius Caesar had done before him with Quintilis (July).

The Feriae Augusti, was first instituted on August 1st by Emperor Augustus as a day of rest, and joined a series of public holidays and festivities that fell in the same month that celebrated the harvest. Together these celebrations provided a long period of rest after weeks of intense agricultural labour. Farmers and laborers, having completed their most intensive work of the year, finally had a period of respite. An essential break for the rural economy, allowing workers to recharge and prepare for the next cycle of agricultural activities. Landowners would often host feasts for their labourers, which would serve as a reward for their hard work, but also reinforced social bonds and hierarchies within the rural community.

Festivities included a range of public events such as parades, gladiatorial games, and theatrical performances, which were intended to foster a sense of unity and loyalty among the Roman populace. As well as, horse racing, which were organised across the Empire. These races attracted large crowds and provided a thrilling spectacle of speed and skill. The inclusion of these games in the Feriae Augusti festivities underscored the holiday’s connection to leisure and public enjoyment, aligning with Augustus’s efforts to present himself as a benevolent ruler dedicated to the well-being of his people.

Thus, the establishment of the Feriae Augusti, reinforced Augustus’s image as a leader who brought peace and prosperity to Rome. The holiday also brought unity to the various social classes, from urban citizens enjoying public games to rural laborers partaking in harvest feasts.

The Christian Period

As Christianity spread across the Roman Empire, many already established roman festivals were adapted and repurposed to fit the new religious framework. Ferragosto was no exception. The early Christian Church often sought to align its own calendar with existing festivals, to ease the transition for converts and maintain social cohesion. This strategy led to the incorporation of Ferragosto into the Christian liturgical calendar as the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

The move shifted the day of celebration from the 1st August to the the 15th August, the day chosen to commemorate the Virgin Mary’s bodily ascent to heaven. This belief, although not explicitly detailed in the Bible, became a significant doctrine in Christian theology, symbolising Mary’s purity and her unique role in salvation history. The feast was formally defined as dogma by the Catholic Church in 1950 by Pope Pius XII, but it had been celebrated for many centuries prior.

By the Middle Ages, Ferragosto, was celebrated primarily as the Feast of the Assumption, it retained many of its older elements, such as feasting and communal gatherings, but also introduced new religious observances, which typically included mass, processions, and other religious ceremonies. The religious events were often followed by communal feasts, which reinforced social bonds and provided an opportunity for rest and relaxation.

The Renaissance period saw a further refinement of Ferragosto celebrations. The renewed interest in classical antiquity brought a greater awareness of the festival’s Roman origins, while the flourishing of religious art and culture enhanced the celebration of the Assumption. Renaissance processions became more elaborate, often featuring pageantry and artistic displays that highlighted both religious devotion and civic pride.

In many Italian cities, the Assumption was marked by grand processions through the streets, with participants carrying statues of the Virgin Mary adorned with flowers and candles. These processions often culminated in the central square, where the clergy would lead the community in prayer and reflection. The involvement of civic leaders and guilds in these celebrations underscored the festival’s role in promoting both religious and social harmony.

Ferragosto During the Fascist Era

The period of Fascist rule in Italy, from 1922 to 1943 under Benito Mussolini, saw significant attempts to manipulate cultural traditions, including Ferragosto, to serve the regime’s ideological goals. The Fascist government sought to control and influence various aspects of Italian life, promoting a unified national identity and leveraging traditional holidays for political purposes.

Mussolini’s regime aimed to create a strong, cohesive Italian identity centred around Fascist principles. To achieve this, the government co-opted existing cultural and religious festivals, and infused them with Fascist propaganda. This manipulation was part of a broader strategy to align popular traditions with the state’s objectives and reinforce the regime’s control over Italian society.

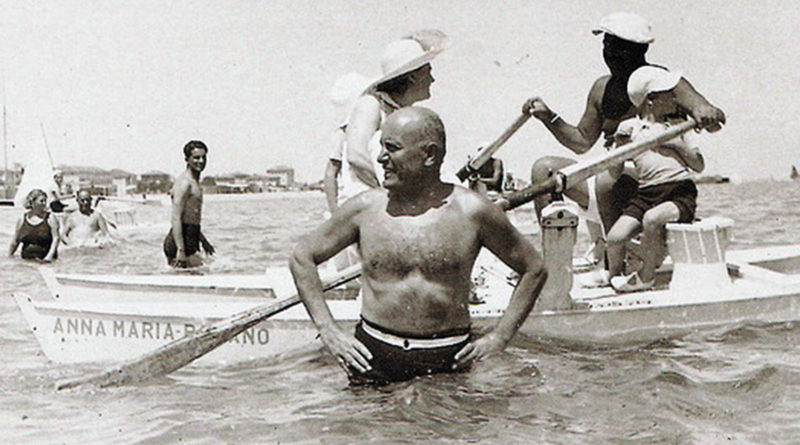

One of the most notable changes to Ferragosto during the Fascist era was the introduction of Treni Popolari (People’s Trains) in the mid-1930s. These special trains were organised by the regime to provide affordable travel for working-class Italians in major city centres, allowing them to enjoy the holiday and promoting the idea of social unity and wellbeing under Fascism.

These People’s Trains were heavily subsidised, making travel to the seaside, countryside, and other vacation spots accessible to a broader segment of the population, including those who had previously been unable to afford such trips. For many, it was the first time that they would be able to see and experience the sea or countryside and they would bring their own food to keep costs down. A practice that has since developed into the modern tradition of the Ferragosto picnic/BBQ. The initiative was heavily publicised and framed as a gift from the regime to the Italian people, highlighting Mussolini’s commitment to improving the lives of ordinary citizens. Posters, newsreels, and other media depicted happy families enjoying their Ferragosto vacations, reinforcing the image of a benevolent and efficient government.

The Fascist regime also organised a variety of leisure activities during the period, such as sporting events, parades, and also festivals and fairs, all in an attempt to promote the regime’s narrative of national strength and revival by emphasising physical fitness, military preparedness, and nationalist pride.

While the Fascist regime sought to co-opt Ferragosto for its own purposes, the religious aspects of the holiday remained significant for many Italians. The Church continued to celebrate the Feast of the Assumption with masses, processions, and other liturgical events. However, the regime’s emphasis on secular celebrations sometimes created tensions between religious and state-sponsored activities.

In many cases, religious and secular celebrations coexisted, with Italians participating in both church services and state-organised events. This dual participation reflected the complex relationship between the Fascist state and the Catholic Church, which involved both collaboration and conflict.

The Fascist manipulation of Ferragosto left a lasting impact on the holiday, shaping its modern character in several ways. For instance, the regime’s efforts to make travel and leisure activities accessible to the working class had a democratising effect, laying the groundwork for the widespread vacation culture that characterises Ferragosto today. And the use of Ferragosto to promote national unity and pride has also endured, with the holiday continuing to serve as a symbol of Italian identity and communal celebration.

Post-War Developments and Contemporary Celebrations

After World War II, Italy underwent significant social, economic, and cultural transformations that profoundly influenced the celebration of Ferragosto. The period following the war, often referred to as the ‘Italian economic miracle’, spanning roughly from the 1950s to the early 1970s, saw rapid industrialisation, urbanisation, and improvements in living standards, which brought about significant changes in Italian society.

As many Italians moved from rural areas to cities in search of better job opportunities and living conditions, urban centres expanded and a more interconnected national economy was created. With rising incomes and improved standards of living, more Italians were now able to afford leisure activities and vacations.

This greater financial stability and the advent of paid time off, made Ferragosto synonymous with leisure and travel. The tradition of Ferragosto al mare (Ferragosto at the beach) emerged as Italians increasingly sought to escape the heat of the cities and spend their holiday on the coast. Coastal towns and beach resorts experienced a surge in popularity as tourism became a major industry. Iconic destinations like the Amalfi Coast, Rimini, and the islands of Sicily and Sardinia attracted large numbers of visitors during the Ferragosto period.

Despite the emphasis on travel and leisure growing, the tradition of family gatherings and communal feasts remained a cornerstone of Ferragosto celebrations. Families would often host barbecues, picnics, and outdoor meals, taking advantage of the warm summer weather. These gatherings provided an opportunity for relatives to reunite, share stories, and enjoy each other’s company.

The rise of mass culture and media in the post-war era has also played a big role in shaping the public view of Ferragosto and its modern traditions.

The proliferation of television and radio brought Ferragosto celebrations into people’s homes, with special broadcasts featuring music, comedy, and cultural programming. Along side this, the Italian film industry, produced numerous movies that depicted Ferragosto as a time of joy, relaxation and romance, and advertising campaigns by travel agencies, food companies, and consumer brands capitalised on the holiday spirit to promote their products.

Even though Ferragosto became more and more secularised, the religious significance of the Assumption of Mary remained important, though as always adapted to the social and cultural changes of the time. For instance, in urban areas, religious processions and masses continued to be held, but they were often complemented by secular festivities such as concerts, fairs, and fireworks displays.

Nowadays, Ferragosto is a public holiday that marks the peak of the summer season, and continues to be characterised by a blend of religious and non-religious activities.

The family feast is one of the most enduring traditions of Ferragosto. Italians across the country will often gather with relatives and friends to share meals that feature seasonal and regional dishes. These feasts are occasions for bonding and celebration, reflecting the importance of family in Italian culture, they will often be enjoyed outside as families and friends flock to the coast or the countryside, a legacy of the Fascist period.

The period of Ferragosto is also a time with plenty of local festivals, which celebrate regional specialties and cultural heritage, with food stalls, music, dance, and traditional games. Fireworks displays are now a spectacular highlight of many Ferragosto festivals, lighting up the night sky and adding to the festive atmosphere. In some towns, these displays are accompanied by musical performances and other entertainment, drawing large crowds and fostering a sense of community pride.

Nevertheless, the religious aspect of Ferragosto remains significant, with many Italians attending mass and participating in processions to honour the Assumption of Mary. In some regions, these religious events are particularly elaborate, featuring ornate decorations, special liturgies, and large gatherings of the faithful. Churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary often hold special services, and it is not uncommon for towns to organise pilgrimages to local shrines or other holy sites.