Pasta, a masterpiece of culinary engineering, simple, yet versatile, a cornerstone of Italian cuisine and Italy’s most famous and successful exports. Yet, a product not exclusive to Italy. Many countries have their own pasta dishes, developed independently to Italy, despite this no other country has made pasta part of their personality and culture. Think of Italy, you think of pasta. Think of pasta, you think of Italy. From the trattorias of Rome to the family kitchens in New York, pasta has become synonymous with Italian food culture. It simply captures the essence of Italy.

Boasting a history that goes back more than a thousand years, pasta is deeply intertwined with Italy’s cultural and culinary evolution. Contrary to the popular romanticised myth of Marco Polo introducing pasta to Italy from China, which originated from a 20th century marketing campaign, pasta had already been a part of Italy’s culinary landscape long before Polo’s time, with its origins in Italy considered to have been independently developed. Nevertheless, China does have an older pasta tradition, thus, the ‘first pasta’ was technically made in China. The earliest evidence of Chinese noodles appears to be an unearthed bowl of noodles made from millet dating back 4,000 years, over in Italy, however, the evolution of pasta may have occurred more slowly, and is developed from durum wheat semolina.

As humans began to cultivate wheat, and the subsequent discovery of its potential when mixed with water, the creation of pasta was perhaps inevitable. While the exact origins of pasta in Italy, and the Mediterranean in general, are often debated and shrouded in mystery, its development can be clearly traced back to several ancient cultures.

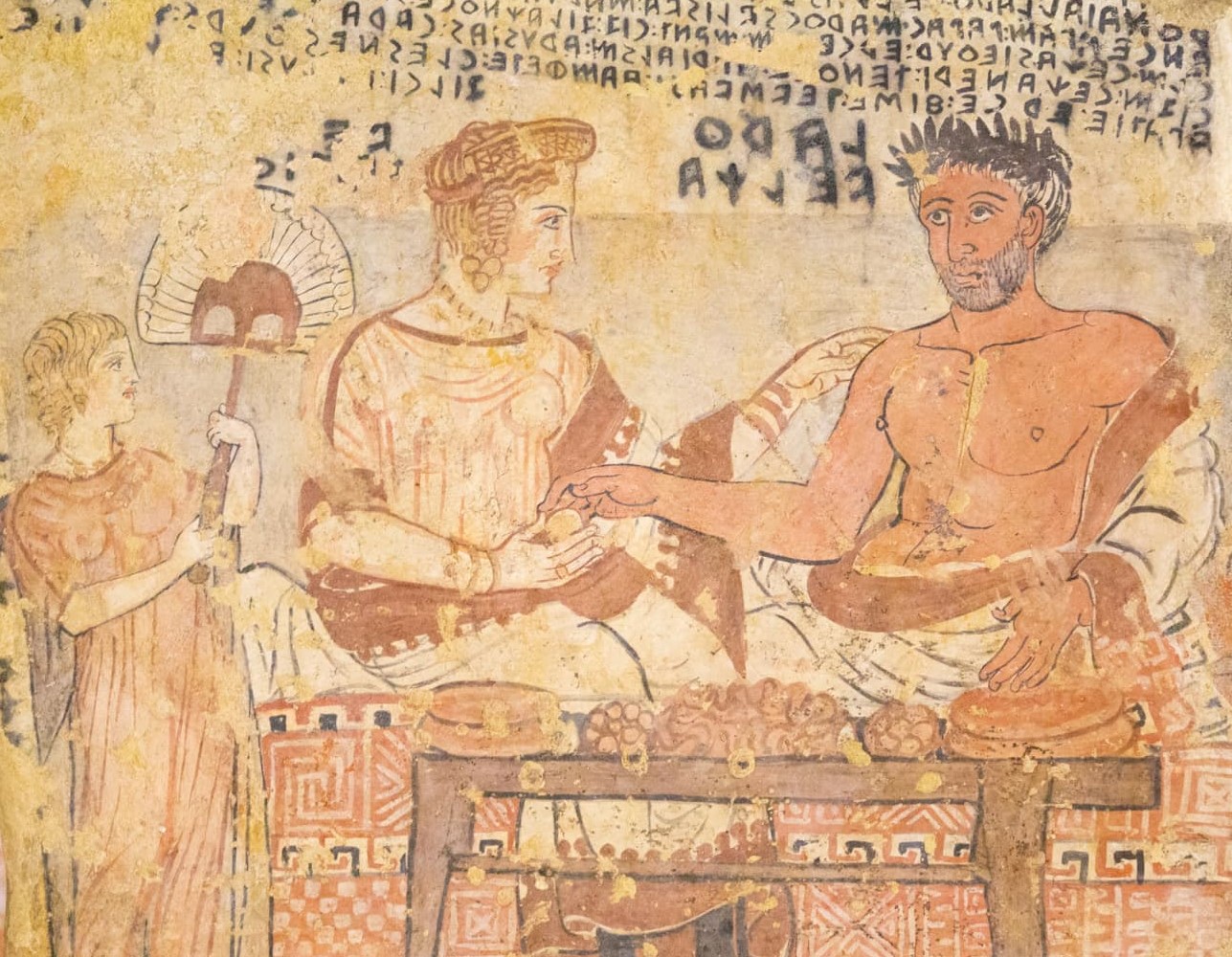

The Etruscans, who inhabited what is now Tuscany, created a lasagne-type dish made from spelt flour and water around 400 B.C. This dish bore a resemblance to modern pasta, although it was likely more rudimentary. Archaeological evidence, such as tomb paintings and ancient tools, suggests that the Etruscans had a rich culinary tradition, with pasta-like preparations playing a significant role in their diet.

The Ancient Greeks and Romans also played a part in this story. The ancient Greeks had a dish known as itrion made from wheat flour and water, while the Romans enjoyed lagana, perhaps an early ancestor of lasagne.

In writings dating back to the 1st century BCE Horace, mentions laganum, which is described as thin sheets of fried dough, and a few centuries later, Athenaeus of Naucratis provides a recipe in his Deipnosophitae, for a dish called lagana, described as fine sheets of dough made from wheat and crushed lettuce juice, flavoured with spices, and deep-fried in oil. Though not technically pasta as we know it – a dough boiled in water –, these early forms laid the foundation for its development.

Lagana appears in writings over the successive centuries, to describe similar variations of dough-based foodstuff, and in the fifth century, a cookbook describes a lagana dish where thin sheets of dough are layered with a meat stuffing. However, up until about the sixth and seventh centuries none of the cooking methods described corresponded to our modern-day idea of pasta, boiling it in water. It wasn’t until Isidore of Seville, in his writings around the sixth and seventh centuries, mentioned a definition of lagana that more closely resembles our ideas of pasta, describing a flat bread, which is first cooked in water and then fried in oil.

The Greek word itrion mentioned in the 2nd century by Galen of Pergamon, was described as a homogenous compound of flour and water. This word is thought to have developed into what the Arabs later called itriyya. We find the word itriyya defined in a 9th century dictionary by the Syrian physician Isho Bar Ali as stringlike dough made of semolina and dried before cooking. Then, in the 12th century, writing in his native language while at the court of the Norman King Roger II of Sicily, geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, describes how vast quantities of itriyya were being exported from Sicily across the mediterranean during this time.

At this point, during the medieval period we see pasta begin to resemble more and more modern pasta – a dried dough that was cooked by boiling. By drying the dough, the preservation and exportation of pasta across the Mediterranean was facilitated, thus it became a staple for sailors. The expansion of the Arab world in the early medieval period consequently played a significant role in shaping the pasta we recognise today.